PART 5: RESOURCES

On comfort and foreboding.

Author note: A year ago, I sent out the fourth and final of the earlier essays that made up this newsletter. It was called CHOICE. I deleted the original a few months later–I had to. I intend to eventually explain why. In the meantime: Welcome, or welcome back, to the new iteration of A REASON TO LIVE, the newsletter about interpersonal drama, death, and other inevitabilities.

You can read an archived version of PART ONE: CONFLICT here.

This is PART FIVE: RESOURCES.

THE WEEK before Thanksgiving, I was in a hotel room in Mexico City. It was around noon. Someone knocked on the door: a perfunctory knock, one that announced an intention to enter with little pause into a room presumed abandoned for the day.

Though I had been able to ward off housekeeping that morning, I’d forgotten, again, to hang up the little door knob thingy, the plastic sign requesting solitude. This was a problem, because I had not abandoned my room; I was there–and had been, all morning, and much of the day before–in the big, white bathroom, shitting. My affliction was, of course, the kind of diarrhea foreigners often catch while traveling in Mexico. An illness so violent and unrelenting, you’ve no doubt heard that Mexicans jokingly refer to it as La venganza de Moctezuma–Montezuma’s Revenge–a nod to the king with whom Europeans first made formal contact, sending us payback for Montezuma’s martial and geographic and cultural losses. On my phone, while I was on the toilet, I read the full Wikipedia entry on Montezuma thoroughly, and there was no mention of him having had an excellent sense of humor. But traveler’s diarrhea truly does feel like a ghost inside the intestines, a punishment whose commutation will require something stronger than a land acknowledgement.

Alas, I suspect I can’t claim an ancient Mexican hex was responsible for this particular case of the runs. Among my friends and loved-ones, my chronically weak-stomach and general sickliness are a pair of notorious, plain facts. I am especially prone to falling ill when some expensive fun has been scheduled. (How can one blame the ancient Aztecs with the Ashkenazis so much nearer? The call, as ever, is coming from inside the rectum…)

In Mexico this fall, I’d been sick already for two days, and in the first moments of my illness, had ruined a lovely white nightshirt when I woke up around one a.m. drenched in a cold sweat and could not react quickly enough to the sharp cramp in my lower abdomen. (I’m sorry! I know, I know.)

As such, I was no longer taking any chances, and now sat stark naked upon the commode.

Also, at the time of the knocking, the bathroom door was wide open. (Those of you who live alone, or who are never alone because you have young children, or who are yourselves frequently loose in the sphincter, will think nothing of this. The rest of you may be dismayed. But I assure you, there’s a type of reasonable adult for whom an open bathroom door in a private or even semi-private dwelling is normal.)

I acted as quickly as I could, first to slam the bathroom door, flushing, washing my hands and getting dressed with trembling alacrity into the enormous Nike sweatpants from the shopping mall on La Reforma–a replacement for the crisp cotton nightshirt that was now out being laundered–and a thin heather-gray pocket tee. I had no bra handy. I left the bathroom.

The man who stood now in the vestibule that led into the rest of the room was dressed, as were all staff here, in an old-timey formal costume, like a cartoon butler. His vest was a deep wine color, and matched his bow-tie and the starched cotton handkerchief draped over his stiffly held forearm.

Hello! I am sorry, he said, holding up a white-gloved hand at the sight of my likely pallored face, my disgusting loungewear, and turned to leave. His English was slow and precise but smooth, his Mexican accent utterly appealing, as are–in my opinion–all Mexican accents.

Holding my arms over my un-brassiered chest in an obviously unnatural position, curving my spine downward, tortoise-like, I said, No, it’s okay!

The man said: I have come to clean your minibar.

I saw then that he’d brought along a shiny roller cart, which idled behind him.

Oh, I said. How wonderful.

I don’t know why I didn’t say something more honest. Like, for example: “No, thank you, please leave at once and tell no one of these smells in here.”

I suppose I wanted the fresh teacups and replenished bottled water that would come with a clean minibar. But in my abdomen I felt again the sudden stabbing that announced I had nearly no time to get back to the toilet.

Por favor, please excuse me! Debo usar el baño, I said. I have to use the restroom (repeating in English each phrase I attempted in my imbecile Spanish–a bad habit, for sure–). I rushed back into the bathroom, shutting the door this time with a firm click.

Separated by only an interior wall, I’m sure this guy heard what happened next, and I sensed him hesitate, awkwardly, trying to decide if he was excused from this appalling episode. But, I heard some clinking and rustling, where I suppose he turned to his work at my messy minibar: strewn with dusty spillage from the emptied sachets of probiotic powder–a hardened version of which was also caked at the bottom of the dirtied glasses he was now replacing–and the ripped-open foil packaging from antibiotic tablets, plus several empty bottles of electrolyte drink. These were all treatments a doctor had prescribed me the previous afternoon when the hotel reception sent him–a gentle-natured, small old man in a brown flannel suit who’d come carrying the kind of leather bag the doctor brought to house calls on Nick at Nite–up to the room.

I had loved the doctor–his smooth hands and gentle voice, his tiny stooped back–and wanted to believe him when he’d patted my shoulder and promised me I would be normal again soon, so long as I took the medicines he was ordering for me and didn’t eat any fiber or meat or fat for the next five days.

I know it hurts, he said sadly, referring to my anus, as he added vaselina to the daintily handwritten list of items a bellhop would fetch from the farmacia.

The doctor’s visit had been less than twenty-four hours earlier, but already I was losing hope, unable to banish the thought that this was just my life now. In the vestibule, the man who’d come to clean my minibar and who’d been pretending not to hear my diarrhea departed with a quiet roll of the cart. When I finally left the bathroom later, I saw he’d placed the Do Not Disturb doorknob hanger outside, and lamented that I had been too quickly indisposed to give him a tip.

I took a long shower. I was sick some more. I took another shower, a briefer one, and contemplated the doctor’s advice that I take a hot, soothing sitz bath. But I couldn’t bring myself to bathe in a hotel tub, even one as large and sparkling clean-seeming as the one in my bathroom, which was entirely separate from the shower and–like everything else in the room, like the hotel itself–nicer than that of anywhere else I’d ever slept. But I couldn’t do it. I don’t really understand how baths became associated with luxury, because baths are gross. I was sick again. I took another shower, bringing the antibacterial soap with me, cleansing my hands as though preparing to perform surgery.

Eventually, finally, some reprieve. (In fact, I started to feel nearly better–the doctor had spoken the truth!--but my personality is too cautious and my attitude too negative and my track record too shit-stained to entertain real optimism for a speedy recovery.) An hour went by. I didn’t get sick. I drank some more Electrolit. The horchata flavor was delicious. Another thirty minutes. I didn’t get sick.

I hadn’t eaten, and I knew my traveling companion, who’d left the hotel early that morning to do a solo version of the sight-seeing and meal-taking we’d planned together, was going to insist I try to have just a little something. My head, anyway, ached. I knew I must be hungry, even if I felt no desire to consume any food.

On the hotel phone, the woman from room service was kind. Yes, she said cheerfully, they’d bring me some oatmeal cooked in water even though it wasn’t on the menu after 11 am. Yes, the water would be purified, all the water used for cooking was safe for foreigners to consume. And some white bread toast. And a big bottle of Fiji water. My pleasure, she said when I thanked her.

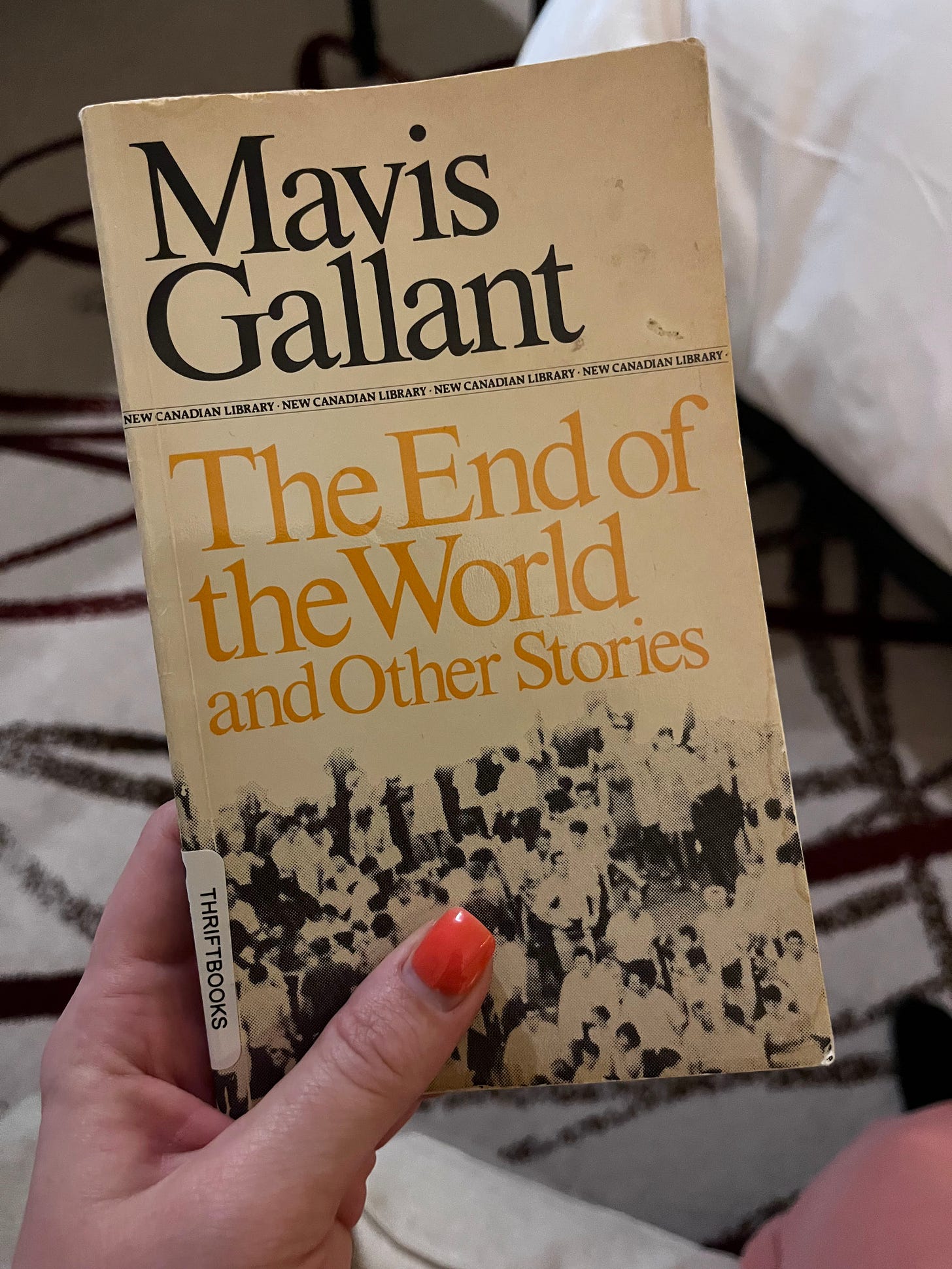

I took the book I always read when I go on vacation (a jaundiced 1982 paperback of some reprinted Mavis Gallant stories, the pages silken from wear) and I sat by the open window overlooking the hotel’s plant-filled, colorfully tiled courtyard. The air was strangely thin without feeling clean; it had a peculiar but not-unpleasant mineral smell, like wet rocks. I read a little, but mostly I watched as the golden afternoon light turned to pinkish dusk against the stone fountain that was the lush courtyard’s centerpiece. Many women stopped on their way past the fountain to do embarrassing, corny poses to (I assume) upload to their embarrassing, corny Instagram accounts. Their boyfriends and husbands and mothers were dutiful, if not entirely satisfactory, photographers. (Several times, a second photoshoot was deemed necessary.) I felt some small notion of jealousy, a sense of failed existence that comes from having nothing sufficiently obnoxious to post to one’s own cringe-worthy social media accounts, especially while on vacation. It passed like the memory that has failed to surface, like a premonition of a feeling. I hated being sick, but there was a large, perverse part of me that didn’t mind being alone, shut up in the room all day.

My bland little meal arrived. I tipped the porter with American money, which was all I could locate in the mess I’d made of the room. He grinned when I asked if he minded, and said, Whatever you want, señora. It is my pleasure.

I waited to get sick again. I looked out the window some more. In the courtyard, a woman wearing a white pantsuit was sitting at the fountain in a big wide-brimmed hat, flanked by two very fluffy gray and white cats: weird, flat-faced purebreds. Fucking Brazilians, I thought with a perfect mixture of admiration and disdain. The cats had little leather harnesses, but nobody was holding onto them. Their leashes fell to the side like Maypole ribbons. They were well-behaved, subdued, but I imagined their confusion at the scene. I wanted to get out the binoculars I’d brought so I could observe their little cat expressions as they watched the water spouting from the fountain, but it didn’t seem like something I could get away with at this hotel. Later, when my companion returned, he reported having met the cats at lunch on the patio. They were named Cleopatrya and Valentino. (She was Brazilian, wasn’t she? I said, too eager, and he said: I thought she was Greek, and shrugged, like: Who gives a shit? I am always guessing, loudly; I’m often wrong.)

DURING my adolescence, I discovered the books that first reeled me toward a life in letters: 19th and early 20th century novels about poor and middle-class people who become, through various strivings or accidents, absorbed into high society. The boys I hung around liked Kurt Vonnegut and Ray Bradbury and Chuck Palaniuk, and, because I was sixteen and didn’t want to be left out, I read those authors and appreciated their inventive narrative structures and tortured humor and general weirdness and even, to a certain extent, their political certitude, but my prevailing sentiment, reading those texts, was one I carry with me today: I am very glad I am not a man, because I get the impression that manhood is very lonely.

What I truly loved to read, I read privately. (Perhaps modern womanhood is lonely, too, and the difference is how many women would prefer to be left alone.) Because we’d all been assigned Jane Eyre and/or Pride and Prejudice and/or A Tale of Two Cities in Language Arts class, my friends–the boys–associated my tastes with the conformity and tyranny of school, and called me a herb and a narc for enjoying our corny, dated homework, with its difficult, old-timey language and bland, out-dated moralizing.

(I didn’t think this was fair; I’d hated plenty of the required reading. I loathed John Steinbeck, for example, and still do. Besides, it wasn’t as though I’d had good grades in any subjects besides History and Language Arts–I failed math and had to attend summer school in 10th and 11th grade… It bothered me how these boys who each had a higher GPA and a more stable home-life could point to such circumstantial details about my preferences in arguing for my lameness. But it’s fine; I forgive them. It was a long time ago, by which I mean: Those smug boys are middle-aged men now, and most of them are completely bald.)

I wasn’t reading in search of some intangible booksmarts; I was reading for the physical material, the texture that was so lacking in my own life’s wobbly scenery. I loved Becky Sharp, that tragic, ruthless bitch, wrapped in the diaphanous gauze of her Clytamnestra costume. And Undine Spragg, and Carrie Meeber in their starched silk dresses, holding up gold plated mirrors to their peaked complections. My interests had little to do with the signs and symbols we were taught to search the pages for, like prizes, in Language Arts class.

At night, at my father’s house, with the noise of the Knicks game blaring from the next room, or Van Morrison on the stereo, my stepmother’s clear voice singing along in perfect time as she cooked, I’d huddle on the twin bed in the corner of my tiny bedroom, which had once been a screened-in porch, and read about ladies who often visited fine hotels. Or, at my mom’s apartment, always pin-drop quiet except for street noise–she was out, or reading her own book, and there was no television, because she’d sent me to Waldorf for primary school and thought television corrupted children–I’d sprawl across the futon with Rebecca. I could see the narrator’s small white hands move from Monte Carlo’s carved gold door knobs to the velvet-drenched sitting rooms of Manderly. That the delicate matter–the crystal chandelier, the tinkling glasses, the ivory-keyed pianos bathed in candlelight–never truly shielded the characters from the chaos and danger and fear and decay and literal haunting that was gunked around their fates like cigarette tar in the lungs of a smoker didn’t bother me at all. In fact, the fact that finery bred no extra happiness, except for the most fleeting, was a great comfort. Early readers of this newsletter already know of my childhood preoccupation with mortality and the meaning of life–a common affliction in the progeny of staunch atheists, as it turns out–and so it goes without saying: I read books with the same air of complacent nihilism I’d already adopted toward the rest of life: Everybody dies, and becomes a corpse, so everybody was the same, and suffering should be expected. What was different, what made people interesting, what made them real, was their stuff.

There’s no way to separate any of this from the fact that my childhood was a liminal one, a half childhood. My parents split up when I was five months old. My dad married my stepmom before I turned two. I spent my childhood moving–before memory set in–between two wildly different households, run by individuals who didn’t like one another and who weren’t willing to pretend otherwise on my behalf. Until I was eighteen, I existed always as an impermanent feature in the places I dwelled, in a state of preparing to soon pack my things back up and spend the other half of my life elsewhere.

I think my early life made me smart, adaptable, and highly skeptical. A little ruthless. Quite unreliable. It has been hard to stay put. I am noncommittal. As such, I love hotels.

I think my two-pronged childhood is also what made me a reader, and therefore: A writer. (Well. Only so much as anything makes a person a writer, besides the sitting down and doing the writing.) I appreciated that I could start reading Vanity Fair at my dad’s house in the suburbs, on the deck overlooking the bird feeders and enormous backyard vegetable garden. I could pick that same novel back up, and still be with it, still be there, with Becky, when I returned to the other planet that was my mom’s various apartments in the industrial outskirts or the nearly gentrified innards of the city, places with cold, creaking hardwood floors and un-working fireplaces, frost coating the inside of window panes, rescue cats climbing all over the counters.

I don’t think it occurred to me that all the novels I loved were about class anxiety and social metamorphosis and dysfunctional family structures until I got to college, where a set of (beloved!) professors all pointed out–seemingly at once–that all the novels I loved are about class anxiety and social metamorphosis and dysfunctional family structures, indeed, that the novel itself is an expression of class anxiety and social metamorphosis and dysfunctional family structures.

I certainly did not realize how, in so many of my favorite novels, there was someone, alone, in a fancy hotel room for which someone else was paying. This character was performing status in a higher social class, or was doing some good old fashioned (for the lack of a less sexist/delightfully rude pejorative) gold-digging, or she was on the run–from a crime, or a man, or a bad thing that happened in a previous, more drab point in her existence–or in the midst of a crime spree, or she worked for some rich people, or she was married to a man who had done well.

But it occurred to me in that hotel room in Mexico City: I had become something of the real version of a type of make-believe person I’d always loved to read about. (I think a lot of writers become, in small ways, the characters who were most preoccupying when their reading minds were still absorptive, pulling together characters–behaviors and quirks and backstories–with the same digestive muscles a young writer uses to evaluate prose, the tenor and quality of sentences (--this is another version of how any young person must accept or reject observable behaviors, distilling what she notices and experiences and how she speaks until her own self is set into the rather tough Jell-O that is the developed adult psyche).

I think this is one of the few things nearly all good writers have in common, and I think it is also one of the reasons so many writers have such a difficult time getting along with one another, and with other highly observant types.

I am not wealthy, and, based on my intentions and interests, I likely won’t ever have much money of my own. But I have a lot of education, and I work in an industry that puts me in proximity to fancier people, and I have no dependents and, as of quite recently, no debts. So I find myself, of late, invited into nicer and stranger places. If I’m not pooping, I have a look around.

THE CURE was playing a sold out concert at a big racetrack inside the 1968 Olympic City park, and Robert Smith and co. were staying at the same hotel. The day before I got sick, I passed through the crowd gathered on the sidewalk outside, fans holding their records, wearing their tour merchandise, hoping for an audience, an autograph. A few of the more bleary-eyed, crazed-looking people appeared to have been waiting by the curb all night.

I was on my way to Coyoacán to see the museum inside Frida Kahlo’s home, Casa Azul, where she lived and worked and was sick nearly her entire life. The museum was brightly tiled with yellow walls and copper cookware in the kitchen, the place was warm and crowded, both with visitors and with Frida Kahlo’s many little things. Though she was a homebody, a symptom of both disability and disposition, Kahlo did travel some, and was a collector of objects from all over, a person who delighted in small ephemera, and who was very much a creature of a physical, tangible world.

The leather handled wheelchair, the carved bed, its macramed quilt, hundreds of decorative plates and figurines and ceramic teapots, the self-portraits. A pair of Diego Rivera’s enormous, paint-stained denim overalls hanging from a door. What I enjoyed most about the museum was the museumless quality it had. In the US, when one visits some similar site of famous or important life–the Biltmore Estate or Herman Melville’s Arrowhead, or, if one is especially corny, somewhere like Colonial Williamsburg, one is met with a deliberate impression of The Past: Here is a place where living happened, but it was much different from living you, modern looker, do in your own ordinary, modern life. Many objects are behind rope, behind glass. This is a practical, rhetorical choice, of course–the people who run Monticello, for example, might have a significant psychological investment in the plantation’s status as a place so old as to be practically mythical, even though we all know it was a prison/torture chamber for the majority of residents during its active era.

But Kahlo’s house felt still alive, lived in, the fact of her life fused to the items on display: her clothes and knick-knacks, not to mention her art.

My favorite room in Casa Azul was in the concrete addition to the original compound, a long, light-filled space Kahlo used as a studio. Roped off with the easels and mirrors were all her paints in tiny glass vials or metal tubes, her case of nubby oil pastels, and her still-crusted with now long-dried paint brushes and the last palette she used–was still using at the time of her death at forty-seven years old–with the paint left, the same as the dirty brushes, like she was coming back for it.

Frida Kahlo spent her entire adulthood in physical pain. Her home was comfortable, well-lit (of course) with soothing, homey decor. It was full of mirrors hung at odd angles, so she could see herself from bed, where she often painted. On display at Casa Azul was a heavy wooden apparatus she’d had fashioned—a peculiar chair, bed, and easel combo—for her mattress. The braces and canes and prosthetics were arranged throughout, leaning against the wall or lying on a counter, like tough meat waiting to be cooked.

This book is very good.

WE LEFT Casa Azul and went to the modest museum of the Instituto del Derecho de Asilo. It was just down the street and two blocks over. Leon Trotsky and his second wife, Natalia, along with their son Lev came to Mexico in January 1937. They’d been through quite an ordeal over the previous several years. (Leon Trotsky’s whole life was an exciting, insane ordeal. I highly recommend visiting the Instituto if you go to Mexico City, and/or reading this book and, if you have the attention span: these, and watching this documentary film, which is an excellent example of the under-appreciated phenomenon of high camp in 1990s documentaries.)

In autumn of 1927, a decade after the October Revolution, Trotsky was expelled from the Communist Party and, about a year and a half later, exiled and deported to Turkey. There he was hunted, like an animal in the forest, by Soviet Assassins. The Turkish police surveilled him at all times; Atatürk was distrustful of such a verbose and effective political organizer. The Trotskys sought asylum from the United States, Belgium, France, Germany, England and Denmark. Each country denied their appeal.

Finally, in 1933, France got a new prime minister who said Trotsky could live there. But when he arrived, they said he could live anywhere except Paris. He was, naturally, affronted. In the seaside commune Royan, the French police kept constant surveillance on Trotsky, limiting his movements until he was basically under house arrest. (There is significant evidence that Trotsky spent as much time as possible while in France writing and disseminating literature–often with the help of his friend Simone Weil–encouraging trade workers to take part in mass general strikes. Which they did. I don’t think he could’ve stopped his political activity even if he’d wanted to, and he definitely didn’t want to stop.) When, in 1935, Norwegian painter and politician Konrad Knudson won the Trotskys entrance to that northern nation, he and Natalia left France and went to stay in a farmhouse just outside a small and secluded inland town called Hønefoss.

By this time, Trotsky and his entire family had been stripped of their Soviet citizenship. Back in the USSR, an absent Trotsky had been “tried” for treason and insurrection, found guilty, and sentenced to death. While Trotsky was visiting Knudson at the seashore, some Norwegian fascists broke into the Hønefoss farmhouse and vandalized Trotsky’s letters and writings. High stakes drama ensued, as it had in Turkey and France. It’s all fascinating, but I’ll cut to the chase: In December 1936, Leon and Natalia Trotsky were deported, in a sense, when the Norwegian authorities put them on an oil tanker called the Ruth.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera had been campaigning for Trotsky’s asylum in Mexico, and, finally, the Mexican government granted them stay. The Ruth brought the Trotskys to Tampico, where Kahlo and Diego met them, and they all rode the train together to Mexico City.

The Trotsky’s lived at Casa Azul for two years. Then, apparently, Rivera found out that Trotsky and Frida Kahlo had done a little schtupping, and he was pretty pissed and threw our boy Leon out of the house. (And if you can’t understand why someone in as precarious a circumstance as Trotsky would risk his sanctuary just to have some secret sex with an eccentric curmudgeon like Kahlo, well, I’m not sure a newsletter called A Reason to Live is right for you.)

So. The Trotskys moved down the block.

I’D LOVED both, but preferred Trotsky’s house to Frida Kahlo’s. I’d loved the less manicured quality of the garden, which was spookily quiet, and the modest, borrowed looking furniture and housewares–a rusted tea kettle, the chipped plates–the red-painted floorboards, the stained-glass windows and heavy pocket doors; the kitschy, cheap, creepiness of the shrine with Trotsky’s ashes, the long-emptied chicken coops, and the noticeable lack of other tourists (in contrast with Casa Azul, where we’d waited on a long line despite having made the required reservation).

The place was so sad! But it had the consoling–to me–look of a place a person makes comfortable despite knowing it’s transitional, only temporary. Even if one has a sense of needing to flee. In Kahlo’s studio, I’d experienced a kind of reverent jealousy and regret over the fact that I haven’t saved precious little knick knacks, haven’t cared, the way normal people do, about photographs or sentimental objects. Despite my interest in the material of life–the stuff that lasts–I haven’t taken care to save much of my own.

I am–ha. h.a. ha.–the anal retentive type. I read and then promptly toss cards and notes, and notebooks once they’re full. I give books away, I wear my clothing until threadbare, at which point I usually throw the clothes away, since they are too see-through and pit-stained to donate, and because “donating” clothes to charity (as well as desk lamps that don’t turn on, and frayed beach towels, and expired pantry food) is one of those useless balms people slather on the chapped, stinging surface of their own gross materialism: You just want someone else to take out your trash, because you don’t want to think about how much trash you make. And I’m something of a loser, as well. I mean: I’ve lost things. I have lost two passports and my birth certificate. A great grandmother’s wedding ring. A black silk vintage Betsey Johnson slip dress, which I bought from Andy’s Chee-Pees (IFKYK) with money my stepmother gave me for a prom dress, instructing me to be normal, please, and go Lord & Taylor for one of those spaghetti strap Jessica McClintock numbers everyone else was wearing that year (2000). A few years later, when I was twenty and moving into my first apartment, my mother bought for me as a gift a small wooden dinette table from an antique bazaar downtown, those ones they used to set up in parking lots on nice days. It was lovely, with drop-leaf and matching oak chairs and in excellent condition. I left it in Madison, Wisconsin 10 years later, the winter after I’d finished graduate school. I simply didn’t want the hassle of trying to get it back to New York, I just wanted to get back to New York, and everything else I had was cheap and felt disposable.

In Mexico City, the already prolific Trotsky wrote more than ever before. It was the most productive part of his life, there, the end. In August 1940, a member of Stalin’s secret police, a guy named Ramón, stabbed Trotsky with an ice pick, right through the widest part of the skull.You can’t go all the way into the shabby little room where this happened, but from the stanchioned off entryway, you can see a decaying map of Mexico on the wall, hung over some uncomfortable looking chairs with a wicker seat and a mahogany desk, on top of which are stacks of notebooks, the work he was doing.

What I find most interesting about Leon Trotsky is how he kept writing, even under the most distracting circumstances. What I find most admirable about Frida Kahlo is she could stand the pain she was in because she had work to do, and this work was really, truly weird.

NOW, in the hotel room I could not have afforded to pay for myself, I ate some quickly cooling oatmeal and read snippets from the same Mavis Gallant stories I’d already read a hundred times before—and hope to read another hundred times, at least—and looked out the big window and considered my incredible luck and wondered how soon I’d have diarrhea again.

Later, my companion returned with an armful of lovely, carefully chosen souvenirs—two fine bottles of mezcal, a handmade leather satchel, several attractive children’s picture books—asked how I was feeling.

I’m fine! I said. I haven’t been sick in, like, four hours.

It was true.

He asked if I wanted to go downstairs, take a walk around the hotel’s exquisite grounds, have a tea in one of the open air cafés in Condesa.

I looked at him. I knew what I should say.

I gestured toward the television, blaring, and told him, without apology, that I was already quite busy.

You should go, though! I said, attempting to sound encouraging. And bring me back one of those coconut flavored Gatorades.

He’d been busy all day, had seen the enormous whale skeleton at Biblioteca Vasconcelos, walked Chapultepec, had fresh tortillas under a huge statue of Albert Einstein’s head. All that shopping!

Now he didn't really want to go anywhere, either. I could see it. He felt like he should go out again, do something else, buy more presents for his children, see more. He went to take a long, hot shower.

On television, a giant piece of birthday cake did a sexy little dance and sang an irritating jingle. I watched, rapt, and wondered if I had ever been happier. I looked around at the brochures and bags and tickets scattered. I needed to get rid of this garbage so housekeeping didn’t think I was a slob.

We were leaving soon enough, for home.